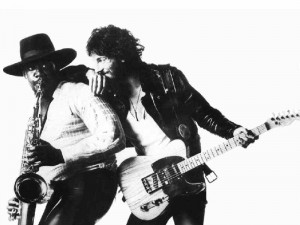

One danger in this and the previous entry is that of conveying the impression that an individual’s life may be reduced to a single mythological or psychological interpretation. Indeed, rather than suggesting that E Street Band sax man Clarence Clemons’ life can be simplified in such a manner, Mythfire wishes to instead use his life as described in friend and bandleader Bruce Springsteen’s eulogy to discuss what it more generally means to live a mythological and/or psychological life. The prior entry introduced the idea that one’s personal mythology – i.e. the meaning (logos) of one’s life story (mythos) – is comprised of eternal energies in the form of basic units and actions. Examples of mythic units include occupations, roles we play when interacting with others, important places or objects, and more. Mythic actions include creation, destruction, birth, marriage, death, salvation, victory, defeat, and even the elaboration ofour personal narrative as we tell it to ourselves and others. (This latter action is called story-telling or “mythologizing.”)

Whatever our personal myth or myths, analytical psychologist Anthony Stevens describes them as “belief systems” that in relation to one’s life circumstances are in the best case effective, adaptive, functional, and appropriate or, in the worst, their opposites.[1] As belief systems they are how we not only understand but give meaning and order to our lives. (Like meaning, understanding and order are other connotations of clarity associated with the word logos.) Importantly, we understand, order, and even create our personal myth in cooperation with what have been called inner and outer fatalities, i.e. inspiration, dreams, life experiences, accidents and chance occurrences, and our vocation or calling. Did Clarence Clemons choose to be “The Big Man,” sax man, a “shaman,” etc. or was he chosen to become these? Most likely it is a combination, or co-operation of the two.

On a moment-by-moment basis on the human plane, these energies operate through and are mediated by the individual soul. This is the meeting point of mythology and psychology – the latter term referring here to meaning (logos) engendered within and experienced by the human soul (psyche). This is not soul understood theologically as that which remains after our physical deaths but soul as that which gives meaning, depth, and breadth to life in the here-and-now. The theological sense emphasizes a material or ethereal substance; the latter psychological sense is more concerned with a present-oriented perspective that yields an experience of significance and importance.

James Hillman has perhaps done more than anyone else to develop this idea of soul and the related term soul-making:

“First, ‘soul’ refers to the deepening of events into experiences; second, the significance soul makes possible, whether in love or in religious concern, derives from its special relation with death. And third, by ‘soul’ I mean the imaginative possibility in our natures, the experiencing through reflective speculation, dream, image, and fantasy – that mode which recognizes all realities as primarily symbolic or metaphorical.”[2]

As mentioned in a previous post, Hillman borrows the term soul-making from poet John Keats who wrote “Call the world if you please, ‘The vale of Soul-making.’ Then you will find out the use of the world…’” To this Hillman adds: “From this perspective the human adventure is a wandering through the vale of the world for the sake of making soul. Our life is psychological, and the purpose of life is to make psyche of it, to find connections between life and soul.”[3]

While Hillman goes on in his Pulitzer-prize nominated Re-Visioning Psychology to discuss in much greater detail four main modes of soul-making, perhaps the above quotes will suffice for the purpose of the present post. Springsteen’s eulogy reveals that Clemons was a man who most definitely knew how to deepen events into experiences; via soul created “significance” in terms of love and a religious concern for life; and knew firsthand “the imaginative possibility in our natures.” Of course, the eulogy itself derives much of its own soulfulness from its “special relation to death,” i.e. the death of The Big Man himself. [4]

Finally, another danger to go along with the one mentioned at the start of this post is the possibility of over-romanticizing or glorifying Clemons. Springsteen goes out of his way to give a full portrait of his friend, revealing him to be not a saint but a “Dark Soul.” In a similar vein, Hillman also takes great effort to enumerate the ways in which our manias or pathologies comprise one of the four primary modes of soul-making. The process which Hillman calls “pathologizing” understands that our afflictions, neuroses, complexes, fears, compulsive behaviors – in other words, our woundedness – reveal our deepest soul needs and wants. Furthermore, this pathologizing process reveals not only our connection to humanity but also divinity:

- “. . . [T]hus pathologizing is a way of moving from transcendental theology to immanent psychology. For immanence is only a doctrine until I am knocked back through symptoms by these dominant powers, and I recognize that in my disturbances there really are forces I cannot control and yet which want something from me and intend something with me.”[5]

Readers of Springsteen’s eulogy get a real sense of this “intention” which preceded Clemons, operated through him, and will last long after he’s gone. On the one hand, his Temple of Soul will continue its soul-making magic every time he is remembered, his music played, and his story told. On the other hand, his impact will be even greater if we are motivated by his example to contemplate our own Temple of Soul and soul-making.

——

Note: In a recent interview on the TV show The View, pop star Lady Gaga paid tribute to Clarence Clemons in terms that are very much in keeping with soul-making as described above: “[Clemons] really changes your life so quickly and it’s very…you don’t know why. You can’t explain it. But he just has this godly spirit about him. You feel like you’re in the presence of something so . . . significant.” This can be found at the 8:30 mark here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAPkwGIgbsI.

——

Next Tuesday: “The Streets of Philadelphia”

[1] Stevens, Anthony. Private Myths: Dreams and Dreaming. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1995: 202. Pages 202-3 cover a section entitled “The Personal Myth.”

[2] Hillman, James. Re-Visioning Psychology. New York: HarperPerennial, 1975: xvi. Italics in the original.

[3] Ibid., xvi.

[4] Springsteen’s eulogy can be found here: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/bruce-springsteens-eulogy-for-clarence-clemons-20110629.

[5] Re-Visioning, 105.