“One, two, three; but where, my dear Timaeus, is the fourth…?”[1]

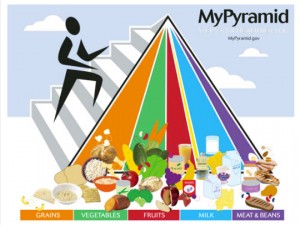

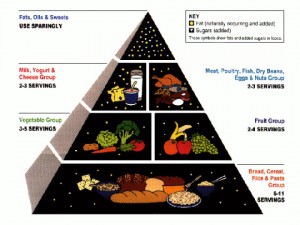

Amid much fanfare earlier this month the United States Department of Agriculture, (USDA) unveiled a new food guide icon with the help of first lady Michelle Obama. Replacing the last two pyramid-shaped images, the new icon – a dinner plate – visually conveys the desired portion sizes of the different components of an ideal meal. One registered dietitian claimed that this new icon is an improvement over the last two because “it allows people to quickly and visually rate their plate and try to get it to look like the icon without measuring or counting.” She continued: “It may not be the magic bullet to get everyone eating right, but it is a step in the right direction — a simple and clear tool to promote balance, portions, variety and wholesome food at mealtime.” [2]

The move from the prior pyramid image with its potentially confusing steps to be taken, i.e. measuring and counting, to the more balanced and “wholesome” iconic round plate might aid not only our physical health but also – at least symbolically – our understanding of a psychological concept discussed at some length by C.G. Jung and later psychologists: the progression of collective Western stages of consciousness as symbolized in the move from the number three to the number four.[3] (To casual readers, the triangular pyramid no doubt readily lends itself to associations with the number three; although Jung wrote extensively on correlations between the number four, or quaternities, and the figure of the circle, the less obvious connection of these two concepts will have to be assumed by the reader for purposes of brevity.) [4]

On the move from three to four, Mythfire would like to quote from Jungian analyst Robert Johnson’s He: Understanding Masculine Psychology, published in 1989:

“In 1948 and 1949, [Jung] was jubilant at the new dogma of the Catholic church which placed the Virgin Mary with the Trinity, all masculine figures, in Heaven. He felt that this completed an earlier, incomplete stage of development that had brought so much unrest and conflict to the western world. The symbol precedes the fact by many years, which indicates that the possibility is now open to us; but the work is not yet done.” [5]

Johnson continues:

“Dr. Jung felt that the work of a truly modern person was to make the expansion of consciousness represented by the evolution from three to four – from the consciousness devoted to doing, working, accomplishing, progressing to that characterized by peace, tranquility, existential being. The heart of the matter is that four can contain three, but three can not contain four.”[6]

He then concludes:

“We are apparently in an age where the consciousness of man is advancing from a trinitarian to a quaternarian view. This is one possible and profound way of appraising the extreme chaos our world is now in . . . . This suggests we are going through an evolution of consciousness from the nice orderly all-masculine concept of reality, the Trinitarian view of God, toward a quaternarian view that includes the feminine as well as other elements that are difficult to include if one insists on the old values.”[7]

If one keeps in mind Johnson’s line that the “symbol precedes the fact by many years,” then we might see how “the extreme chaos our world is now in” continues today to be the struggle to realize the development in consciousness symbolized by the dogma of the Assumption of Mary (which Pope Pius XII actually established as church doctrine in 1950). The riots and revolutions of the Arab Spring, an “historic step” forward by the U.N. in recognition of gay rights, the ongoing New York and California gay marriage legislative and court cases, and debates over “green” energy sources versus fossil fuels – all ripped from last week’s headlines – give ample testimony of new “elements” and “values” that are being insisted upon as part of this more rounded, balanced, and inclusive stage of consciousness we are collectively struggling to enter. [8]

Johnson captures Mythfire’s idea of the pyramid-to-plate analogy when he later states how “[i]t seems that it is the purpose of evolution now to replace an image of perfection with the concept of completeness or wholeness.” [9] In sum, that which has been rejected, oppressed, missing, or in some way neglected must be recognized and integrated as valuable in its own “portion” because of its diversity or “variety” if a harmonious “balance” and “wholeness” are ever to be realized, i.e. to be made real. This is what it means to make the move from the three of the pyramid to the four of the circle.

What are additional examples of this epochal shift toward new elements or values of wholeness and completion? See footnote #10 for some of Mythfire’s thoughts.[10]

——

Addendum: Like Johnson, analytical psychologist Edward Edinger stresses that we can experience “the developmental, temporal process of realization,” i.e. the steps of the three without necessarily ever achieving the “structural wholeness” and “completion” of the four, but we cannot achieve or maintain the four without the steps of the three: “Fourness, or psychic totality, must be actualized by submitting it to the threefold process of realization in time. One must submit oneself to the painful dialectic of the developmental process.” So, even if a round dinner plate symbolically serves as the goal of our physical or psychological well-being, we may very well still find that this well-being is only realizable via the measured and not infrequently painful steps indicated in the earlier icons. See chapter 7 in Edinger’s magnum opus Ego & Archetype for more on the move from three to four.

——

Next Monday: The Enigma of Numbers (“From Three to Four – Part 2”)

[1] Socrates’ opening line to Plato’s Timaeus. Jung references this opening line multiple times when discussing the move from three to four. For a succinct psychological explication of this Socratic opener, see p. 191 in The Enigma of Numbers — a book which is the focus of the following (June 27th) Mythfire post.

[2] http://yourlife.usatoday.com/fitness-food/diet-nutrition/story/2011/06/Government-replaces-food-guide-pyramid-with-a-plate/47892250/1

[3] The move from three to four also figures into the stages of consciousness of an individual as well as the collective, perhaps most evidently in terms of a person’s typological development. Typologically, the missing fourth is the person’s inferior function which needs to be developed in harmony with the other three functions.

[4] For Jung’s references linking the #4 and the figure of the circle, multiple entries can be found in the Index to the Collected Works under “quaternity,” sub-heading “and circle.”

[5] Johnson, Robert A. He: Understanding Masculine Psychology. Rev. Ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1989: 63.

[6] Ibid., 63-4. See also above “Addendum.”

[7] Ibid., 64.

[8] For the U.N. resolution: http://security.blogs.cnn.com/2011/06/17/u-n-passes-historic-gay-rights-resolution/.

[9] Ibid., 64.

[10] The recent worldwide popularity of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code speaks to a deep-seated feeling that the feminine as a powerful energic and emotional dynamic has long been neglected and needs to be recognized and integrated. The increased presence of women as well as gays and other minorities in positions of power – in church, business, government, and military – reflects a similar recognition. Finally, Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth resonates in no small part because it too speaks a truth – in this case an ecological one – which has been but can no longer be denied, avoided, wished, or rationalized away.