In a remarkable wide-ranging 1912 interview in The New York Times entitled “America Facing Its Most Tragic Moment” C. G. Jung claimed that men in the United States possess an inherent brutality which they repress beneath a veneer of chivalry and prudery. Such repression, or self-control, makes possible the pioneering spirit, business success, and philanthropic generosity for which the U.S. is known. It also leads to savagery and inequality in relation to minorities, including women.

In a remarkable wide-ranging 1912 interview in The New York Times entitled “America Facing Its Most Tragic Moment” C. G. Jung claimed that men in the United States possess an inherent brutality which they repress beneath a veneer of chivalry and prudery. Such repression, or self-control, makes possible the pioneering spirit, business success, and philanthropic generosity for which the U.S. is known. It also leads to savagery and inequality in relation to minorities, including women.

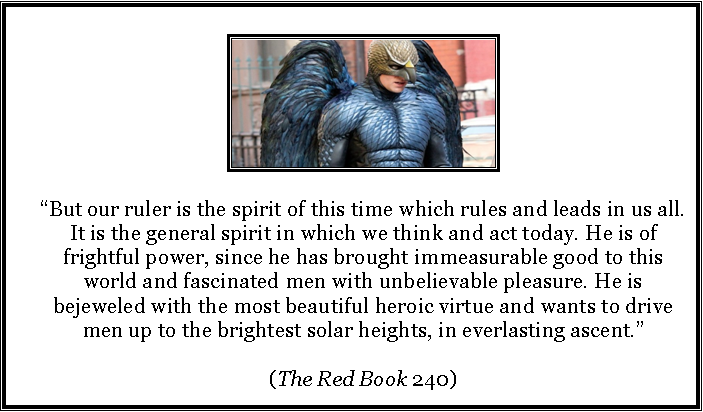

Jung foresaw two possible outcomes to this situation. Americans will be devoured by the machinery and way of life which are products of their inherent brutality, or they will more consciously engage their emotional and instinctual selves to “produce a race which are human beings first, and men and women secondarily.” This latter development shall be known in part through the art and literature of the newly transformed American citizenry. In Visible Mind: Movies, modernity and the unconscious Jungian analyst and writer Christopher Hauke describes this development as a move toward an “über-humanity” (61).

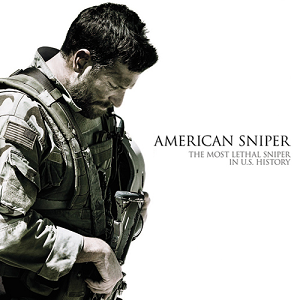

Current events suggest that such a transformation in American society is yet to occur one hundred years (and change) after the publication of the Jung interview. However, signs of progress can be found. The present post turns for support to Clint Eastwood’s recent film American Sniper (2014) which was adapted from the 2012 book of the same title.

Eastwood’s film starts in the streets of Fallujah, Iraq. U.S. Navy Seal and sniper Chris Kyle occupies a rooftop position which enables him to keep a protective eye trained on the Marine Company below him. Kyle watches as a woman emerges from a building and hands a grenade to an adolescent boy at her side. The boy begins to walk in the direction of the advancing Marines.

The film narrative abruptly cuts to an extended flashback sequence involving Kyle’s childhood, military enlistment, Seal and sniper training, and marriage. When the sequence concludes, Kyle is back atop the roof in Fallujah. The grenade-wielding boy moves toward the Marine Company and Kyle has to shoot and kill him as well as the woman when she picks up the grenade. Though Kyle’s radio crackles with congratulations from the Company Commander and another officer, he appears sickened by what he has had to do.

Kyle experiences many tests and challenges over the course of the film with the most overt of these being his desire to stop a Syrian sniper named Mustafa. He also has to learn to adapt to life both in the battlefield and back home. The latter re-entry proves particularly difficult, but by the end of the film he discovers that emotional attunement, presence, and empowerment are by-products of helping others in need whether those others are wounded war vets or his own wife, son, and daughter.

Kyle experiences many tests and challenges over the course of the film with the most overt of these being his desire to stop a Syrian sniper named Mustafa. He also has to learn to adapt to life both in the battlefield and back home. The latter re-entry proves particularly difficult, but by the end of the film he discovers that emotional attunement, presence, and empowerment are by-products of helping others in need whether those others are wounded war vets or his own wife, son, and daughter.

Kyle’s transformation from a hardened sniper with one hundred and sixty confirmed kills to a warm and engaged family and community member is moving and irrefutable. It is also at odds with the traditional masculine hero found in most Hollywood films or for that matter American society. As Jung noted in his interview “You have in America the wooden face […], because you’re trying so hard to hide your emotions and your instincts.” Hauke alludes to this same face as “a type of male stoicism and flattening of emotional expression” (59). Almost any film with Eastwood in a starring role reveals such a stoic flat expression – which makes his late-in-life helming of American Sniper all the more noteworthy.

Current events around the time of the wide release of Eastwood’s film suggest that the American heroic ideal is in extremis. News anchor Brian Williams and political commentator Bill O’Reilly came under fire for telling tall tales about their own supposed heroic exploits. Alex Rodriguez returned to baseball spring training after a year-long ban caused by his use of performance enhancing drugs, and in a failed attempt to remain out of the public eye Lance Armstrong let his wife take the blame for driving into parked cars near their home. The hero most definitely is in the cross hairs. Even the real life Chris Kyle has not been immune from such criticism.

Eastwood’s American Sniper shows the way past such bravado to the heroism needed in the new millennium, i.e., the heroic choice to become emotionally vulnerable and attentive to physical and psychological wounding. Additionally, near the end of the film the scenes of Kyle reconnecting with his family suggest that an instinctive love for and play with others is also of great import. Horsing around at home with his wife before leaving on his final fateful outing, Kyle is living proof that laughter shared with another human being can be restorative and healing. In time such sharing may also help lead to the more humane race predicted by Jung.