Both a legend from the Bible and a dream from one of the 20th century’s more infamous murderers were compared in last week’s post to dreams and visions of alleged Tucson shooter Jared Loughner. In all cases, it would seem that the person concerned succumbed to a powerful and deluded fantasy of superiority over others and even a right or obligation to act out this superiority in specific ways, including the taking of human life. The temptation to greater and even seemingly unlimited power is known as the power principle in psychology; in at least its extreme forms most theological traditions would no doubt look upon this as a temptation to “sin.”

Both a legend from the Bible and a dream from one of the 20th century’s more infamous murderers were compared in last week’s post to dreams and visions of alleged Tucson shooter Jared Loughner. In all cases, it would seem that the person concerned succumbed to a powerful and deluded fantasy of superiority over others and even a right or obligation to act out this superiority in specific ways, including the taking of human life. The temptation to greater and even seemingly unlimited power is known as the power principle in psychology; in at least its extreme forms most theological traditions would no doubt look upon this as a temptation to “sin.”

Mythfire would like to reiterate a point mentioned toward the end of the previous post: the phenomenon of dreams and dreaming is experienced by all of us – even if we do not always remember our dreams – and need not be a harbinger of madness. However, anyone who begins to reflect on his or her dreams and their import is nevertheless struck by a most unsettling notion: what we normally think we know about ourselves, who we are, and who is in control or “running the show” is itself an incomplete and even misguided fantasy. [1]

Following in the footsteps of his renowned colleague Sigmund Freud, Swiss psychiatrist C.G. Jung explored the idea that each of us possesses and/or is able to access what has been called the unconscious. Herein are stored repressed or forgotten memories, instincts, fears, and desires. However, it is also through the unconscious and dreams in particular that we are instructed how to proceed away from madness and unconsciousness toward healing and self-realizing wholeness, a process defined in an earlier Mythfire post as individuation.

All of the Mythfire posts on some level struggle with the question of how do we become more conscious and less unconscious beings? How can we move toward healing and wholeness and away from their opposites? The present entry will attempt to address this eternal conundrum by comparing two of Jung’s dreams with the dreams and visions offered last week. These two dreams were selected both because of the prominence of tree imagery in them but also because they occurred at a period in Jung’s life characterized by upheaval and at times even potential psychosis.

As Jung neared his 39th birthday in the spring and summer of 1914, he had the same dream on three separate occasions. The dreams involved “an Artic cold wave” descending over the land in the middle of summer. All of the land was frozen, turned to ice, and “[a]ll living green things were killed by frost.” The third time Jung had this dream, however, there was a different ending:

“In the third dream frightful cold had again descended from out of the cosmos. This dream, however, had an unexpected end. There stood a leaf-bearing tree, but without fruit (my tree of life, I thought), whose leaves had been transformed by the effects of the frost into sweet grapes full of healing juices. I plucked the grapes and gave them to a large, waiting crowd.”[2]

The second of Jung’s dreams to be discussed occurred thirteen years later and is longer and equally if not more vivid. It is referred to as the “Liverpool Dream”:

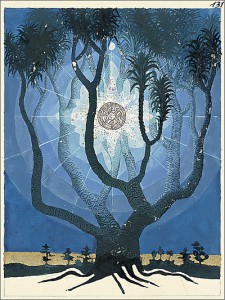

“. . .I found myself in a dirty, sooty city. It was night, and winter, and dark, and raining. I was in Liverpool. With a number of Swiss – say, half a dozen – I walked through the dark streets. I had the feeling that there we were coming from the harbor, and that the real city was actually up above, on the cliffs. We climbed up there. It reminded me of Basel, where the market is down below and then you go up through the Totengasschen (“Alley of the Dead”), which leads to a plateau above and so then to the Petersplatz and the Peterskirche. When we reached the plateau, we found a broad square dimly illuminated by street lights, into which many streets converged. The various quarters of the city were arranged radially around the square. In the center was a round pool, and in the middle of it a small island. While everything round about was obscured by rain, fog, smoke, and dimly lit darkness, the little island blazedwith sunlight. On it stood a single tree, a magnolia, in a shower of reddish blossoms. It was as though the tree stood in the sunlight and were at the same time the source of light. My companions commented on the abominable weather, and obviously did not see the tree. They spoke of another Swiss who was living in Liverpool, and expressed surprise that he should have settled here. I was carried away by the beauty of the flowering tree and the sunlit island, and thought, ‘I know very well why he has settled here.’ Then I awoke.”[3]

The mysteries and meanings of a single dream, much less two dreams, cannot be satisfactorily explored and amplified in one blog post. For the purpose of this entry – which is to suggest that dreams point the way to healing and wholeness – Mythfire will offer Jung’s own analyses of the two dreams just quoted followed by a few more general observations on the phenomenon of dreaming itself.

As stated, the “tree of life” dream occurred in the spring and summer of 1914 and followed other similarly powerful and apocalyptic visions which Jung had in the fall of 1913. In other words, Jung had these dreams and visions in the months leading up to the outbreak of World War I in August 1914:

“On August 1, the world war broke out. Now my task was clear: I had to try to understand what had happened and to what extent my own experience coincided with that of mankind in general. Therefore my first obligation was to probe the depths of my own psyche.”[4]

Generally speaking, most dreams we have speak to our own situation in life at the time the dream occurs. However, occasionally we might have what is sometimes called a “big dream” which addresses not only our individual situation but the collective/cultural one as well. (An additional point about dreams is that while they usually concern a present situation they sometimes also foretell a future one. In dreams as with the psyche both time and space are relative.) Here, in Jung’s “tree of life” dream, and as suggested in the last quote, the sweet grapes symbolize the fruit of labors upon which Jung was only just embarking. As time progressed he would increasingly share these fruits with others in the form of his analytical psychology.

Readers are referred to Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections for a longer analysis of his later “Liverpool” dream. Unlike the collective “big dream” element to his “tree of life” dream, however, the Liverpool – or “pool of life” – dream speaks more to his individual situation at that time in his life:

“This dream represented my situation at the time. I can still see the grayish-yellow raincoats, glistening with the wetness of the rain. Everything was extremely unpleasant, black and opaque – just as I felt then. But I had had a vision of unearthly beauty, and that was why I was able to live at all. Liverpool is the ‘pool of life.’ The ‘liver,’ according to an old view, is the seat of life – that which ‘makes to live.’”[5]

Jung continues on to note that this dream brought with it an experience of “orientation and meaning” and that “[t]herein lies its healing function.” [6] Historians of analytical psychology refer to the period of Jung’s life just prior to his “tree of life” dream and continuing on through and ending with the “pool of life” dream as his “confrontation with the unconscious.” It was a period characterized by dreams, visions, synchronistic phenomena and the disorientation and questioning that these same often bring with them. Again, it has even been said that Jung was on the verge of psychosis during this period.

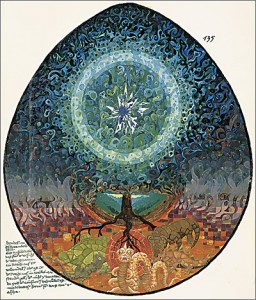

In an effort to document and make sense of these experiences when they happened, Jung engaged in what is called active imagination. He wrote down dialogues with figures from his dreams and visions; he drew or painted images related to what was happening to him, and he kept them along with the dialogues in a large leather bound book. Kept under lock and key and seen by only a handful of individuals over the course of the last half century, the Red Book was finally published last year. The images from this and the last Mythfire posts come from this publication. For example, the “Window on Eternity” image to the right is Jung’s depiction of the “essence” of his Liverpool dream.[7]

So Jung’s artistic endeavors, his active imaginations, helped him to weather the stormy period of his “confrontation with the unconscious.” Equally important to his maintaining a sense of “earthly reality” — the subject of last week’s blog — were his daily obligations to family and patients. Finally, using imagery reminiscent of the African jungle dream also in last week’s post, Jung’s commitment to the science of psychology was another factor which helped him keep his head above water:

“My science was the only way I had of extricating myself from that chaos. Otherwise the material world would have trapped me in its thicket, strangled me like jungle creepers. I took great care to try to understand every single image, every item of my psychic inventory, and to classify them scientifically – so far as this was possible – and, above all, to realize them in actual life. That is what we usually neglect to do. We allow the images to rise up, and maybe we wonder about them, but that is all. We do not take the trouble to understand them, let alone draw ethical conclusions from them.”[8]

This last idea of an ethical conclusion or obligationis very important to analytical psychology’s approach to working with dreams and similar phenomena. One of the reasons this is so is because at the heart of ethics is the realization of membership in a community — a realization which keeps us from succumbing to the power principle’s promise of superiority and dominion:

“Insight into [images] must be converted into an ethical obligation. Not to do so is to fall prey to the power principle, and this produces dangerous effects which are destructive not only to others but even to the knower.”[9]

Mythfire hopes readers see how this present post is a companion piece to last week’s entry. Both discuss the sometimes dangerous and destructive psychic potentials which may overwhelm certain individuals more so than others. In his life and work, Jung showed not only these “certain” individuals but all of us a way to proceed through such jungle thickets of the psyche toward greater healing and wholeness.

——

Next Monday: An Interlude on March Madness

[1] An earlier Mythfire post stated that Jung referenced a transpersonal agency called the “self” or “Self,” comparable in numerous respects to “God” as understood in various religious traditions, as the source of dreams and their messages. Thus, one of the more oft-quoted statements of Jung, “…the experience of the self is always a defeat for the ego,” speaks to the disorientation and humbling relativization of the human ego upon experiencing non-rational phenomena such as dreams, visions, and synchronicities. (CW 14: 778)

[2] Jung, C.G. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Recorded and edited by Aniela Jaffe. New York: Vintage Books, 1989: 176.

[3] Ibid., 197-8.

[4] Ibid., 176.

[5] Ibid., 198.

[6] Ibid., 199.

[7] Ibid., 197. Also, Jung wrote that “The years when I was pursuing my inner images were the most important in my life – in them everything essential was decided. It all began then; the later details are only supplements and clarifications of the material that burst forth from the unconscious, and at first swamped me. It was the prima materia for a lifetime’s work.” (Ibid., 199). Because it is the repository of these “essential” images and ideas, the Red Book is already viewed as a central publication in the annals of analytical psychology.

[8] Ibid., 192.

[9] Ibid., 193.