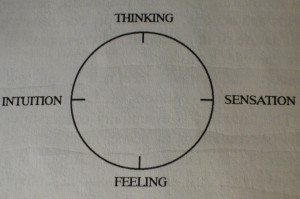

In the last entry, Mythfire put forward the idea that empathy is an example not of personal bias but of an abstract impersonal feeling value which, furthermore, is inseparable from the judicial process. We also argued, toward the beginning of the blog, that some people are innately more feeling-oriented in psychological/typological terms while others are thinking-oriented. This is not good or bad but a fact – a fact, furthermore, which applies to all people including those serving as judges.

In the last entry, Mythfire put forward the idea that empathy is an example not of personal bias but of an abstract impersonal feeling value which, furthermore, is inseparable from the judicial process. We also argued, toward the beginning of the blog, that some people are innately more feeling-oriented in psychological/typological terms while others are thinking-oriented. This is not good or bad but a fact – a fact, furthermore, which applies to all people including those serving as judges.

Perhaps it would be advantageous to provide a clear definition of empathy. President Obama writes on empathy in Audacity of Hope: “It is at the heart of my moral code and it is how I understand the Golden Rule – not simply as a call to sympathy or charity, but as something more demanding, a call to stand in somebody else’s shoes and see through their eyes.”* Compare Obama’s words with those of psychologist Heinz Kohut who in 1984 wrote that empathy means to “experience the inner life of another while simultaneously retaining the stance of an objective observer.”**

Kohut also employed a more technical-sounding yet curiously provocative term for empathy: vicarious introspection.*** Both words in “vicarious introspection” speak to the detached/objective experiencing of the inner life of another and not, as critics might argue, the subjective experiencing of the outer life of another. Empathy as an impersonal feeling value concerns itself with the inner conditions and motives that only later result in outward behavior. Perhaps the idea of empathy as vicarious introspection can offer another way of looking at the blindfold over the eyes of Goddess Justice. She is closing her eyes so as to inwardly and objectively contemplate the life and circumstances of those who enter her realm.

Jung suggests what empathy looks like between a therapist and patient during an analytical hour:

“If the doctor wants to guide another, or even accompany him a step of the way, he must feel with that person’s psyche. He never feels it when he passes judgement. Whether he puts his judgments into words, or keeps them to himself, makes not the slightest difference. To take the opposite position, and to agree with the patient offhand, is also of no use, but estranges him as much as condemnation. Feeling comes only through unprejudiced objectivity. This sounds almost like a scientific precept, and it could be confused with a purely intellectual, abstract attitude of mind. But what I mean is something quite different. It is a human quality—a kind of deep respect for the facts, for the man who suffers from them, and for the riddle of such a man’s life.” ****

Both the phrase “unprejudiced objectivity” and the quote’s last sentence mirror the ideas of empathy and vicarious introspection as discussed above by Obama and Kohut. Professor and psychologist Lionel Corbett goes a step further by linking Jung’s “unprejudiced objectivity” with Kohut’s claim, made elsewhere, that empathy is “value neutral” and “in essence neutral and objective. . . . not in its essence subjection.”*****

Jung’s quote, then, points to both differences and similarities between thinking and feeling as psychological functions. Both thinking and feeling are “neutral and objective” — that is, unbiased — but whereas thinking is the psychological function that operates or judges according to “a purely intellectual or abstract attitude of mind” which most traditionalists prize as “scientific,” feeling, in contrast, judges according to more human concerns and qualities, foremost among them the suffering or plight of the other. Such an understanding of feeling contrasts quite sharply with the contention by critics of Obama and Sotomayor that empathy is tantamount to bias and personal subjective sentiment. As all of these above-quoted thinkers indicate, nothing could be further from the truth — which is why Mythfire has spent considerable time emphasizing and clarifying the point.

Finally, the “Myth and Justice” blog series was inspired in part by the Roman Polanski case, viewing it as an opportunity for discussing the several ideas that were then developed in consequent blogs. In the period of time that has elapsed since the first blog was written, Polanski has been freed from house arrest by the Swiss authorities. This resulted in no small part from the U.S.’s refusal to provide the Swiss with case-related information that could have shown that Polanski had already served his sentence and that “therefore both the proceedings on which the U.S. extradition request [was] founded and the request itself would have [had] no foundation.” Another, tempting, way of assessing this development is to suggest that the “neutral” Swiss, employing something akin to Jung’s (also a Swiss!) “unprejudiced objectivity,” attempted to exercise “a kind of deep respect for the facts, for the man who suffers from them, and for the riddle of such a man’s life.” However, they were rebuffed by the U.S. and its refusal to hand over such “facts.” ******

Perhaps this multi-part chapter of Polanski’s life is destined to always be read in a primarily critical way by the one side, i.e. the spirit soul or thinking type, and in another way by the heart soul or feeling type.

But then again, isn’t this ambiguity and ambivalence in the very spirit — at the very heart — of riddles?

——

Next Thursday: Myth & Justice VI.3 (“In God/dess We Trust?”)

——

*quoted in http://www.huffingtonpost.com/george-lakoff/empathy-sotomayor-and-dem_b_209406.html

**Kohut, Heinz. How Does Analysis Cure?Ed. A. Goldberg & P. E. Stepansky. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984: 175.

***—.The Analysis of the Self.New York: International Universities Press, 1971: 302.

****Jung, C.G. “Psychology and Religion: West and East.”The Collected Works of C. G. Jung:Vol. 11. Ed. H. Read, M. Fordham & G. Adler. Trans. R. Hull. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969: 338.

*****http://www.findingstone.com/professionals/monographs/kohutandjung.htm

******http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/13/movies/13polanski.html?_r=1

This last month the New York Times published an op-ed piece stating that President Obama’s “administration and the Senate leadership should pick up the pace of nominations and confirmations in order to restore some balance to a federal judiciary that was pushed sharply to the right by former President George W. Bush.” * A few days prior to this National Public Radio (NPR) had an unrelated piece about a newly published book on Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. The title of the NPR article was “Scalia Book Explores the Man Behind The Justice” and one glance at included excerpts of the book’s Prologue reveals that his judicial spirit is very much also the jousting spirit mentioned in Mythfire‘s last blog:

This last month the New York Times published an op-ed piece stating that President Obama’s “administration and the Senate leadership should pick up the pace of nominations and confirmations in order to restore some balance to a federal judiciary that was pushed sharply to the right by former President George W. Bush.” * A few days prior to this National Public Radio (NPR) had an unrelated piece about a newly published book on Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. The title of the NPR article was “Scalia Book Explores the Man Behind The Justice” and one glance at included excerpts of the book’s Prologue reveals that his judicial spirit is very much also the jousting spirit mentioned in Mythfire‘s last blog: First, a symbolic primer:

First, a symbolic primer: Finally, Mythfire does believe the following: no matter how much we would like to play out the Polanski case in the media and other forums / courts of public opinion, the case simply and ultimately won’t be played out there. Polanski must return to the U.S. and once again – hard as it may be – stand before the judicial system, the judges and/or jurors who will hear his case. Whether or not Polanski initially gets the verdict he wants, he does have recourse to an appeals system designed to give defendants protection from unjust judicial decisions.

Finally, Mythfire does believe the following: no matter how much we would like to play out the Polanski case in the media and other forums / courts of public opinion, the case simply and ultimately won’t be played out there. Polanski must return to the U.S. and once again – hard as it may be – stand before the judicial system, the judges and/or jurors who will hear his case. Whether or not Polanski initially gets the verdict he wants, he does have recourse to an appeals system designed to give defendants protection from unjust judicial decisions. The last entry discussed the Roman Polanski case in the context of the spirit- and heart- (or blood-) souls dueling within and between both individuals and cultures. Mythfire has had conversations with readers/friends whose very different “takes” on the Polanski case demonstrate these two souls in a most striking fashion. Each side, or soul, is unequivocally and passionately convinced that his/her side is the correct one. Again, the line of argument goes something like this:

The last entry discussed the Roman Polanski case in the context of the spirit- and heart- (or blood-) souls dueling within and between both individuals and cultures. Mythfire has had conversations with readers/friends whose very different “takes” on the Polanski case demonstrate these two souls in a most striking fashion. Each side, or soul, is unequivocally and passionately convinced that his/her side is the correct one. Again, the line of argument goes something like this: