The first entry to this series of blogs on Myth and Justice was entitled “Image is Everything” and concerned how our judicial process is very much a mythic process. The robe worn by the judge in the courtroom transforms him or her into a mythic figure deserving of respect; upon command we “all rise” as one when he/she enters the courtroom. Similarly, this earlier blog entry also observed that recent court cases about the rightness or wrongness of having the Ten Commandments in some concrete form on courthouse property missed the mythic boat by literalizing the psychological energies and ideas underpinning these very mythic images. Both sides – pro and con – were no doubt guilty of this literalizing tendency, forgetful of the fact that before they were a codified religious statement, the Ten Commandments were a psychological/mythic one.

This present entry would like to touch on two more examples of how the judicial process is undeniably mythic. First, if one Googles the slogan “In God We Trust” most likely search results will indicate that the phrase first appeared on U.S. currency during the Civil War and was adopted as the nation’s motto almost one hundred years later. Court cases like those concerning the Ten Commandments have been waged over this motto in recent years by literalists/fundamentalists on both sides of the argument. Should or should not the motto appear on currency? Should or should not “In God We Trust” be emblazoned on many if not most of the courtrooms in the country?

In the view of Mythfire this is a bit myopic. What might seem a perfect example of church and state infringing upon one another’s domains is revealed upon deeper reflection to have mythological underpinnings which preceded and need not be inextricable from organized religion. “In God We Trust” predates not only its first appearance on the U.S. currency but more importantly it predates even Christianity! As just one example, people in the ancient Roman courts of law used to invoke Jupiter as they witnessed the oath. (This energy of appealing to or invoking the idea of divine/cosmic justice and aid has come down to us today in the phrase “By Jove” as well as “In God We Trust.”). The word “god,” for that matter, etymologically means “the one invoked.” Thus, when we declare in a courtroom setting “In God We Trust” we are appealing to or invoking an archetypal notion of cosmic justice rather than a specific deity belonging to one or another religion.

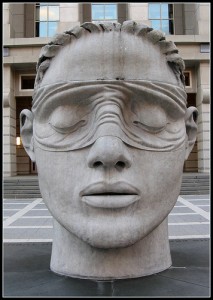

The second example of “justice as mythic” takes us back to the image at the center of this blog series: the statuesque feminine figure of Iustitia, or Themis, as she stands before courthouses around the world. In her we find embodied both the eternal balancing of spirit-soul and heart-soul discussed in the early blogs as well as the thinking and feeling functions discussed in the later blog entries. Perhaps in the end these soul energies and psychological functions are one and the same.

Another way of driving home this point is to look at the word jurisprudence. The standard definition states that jurisprudence is the science or philosophy of law. If we look at the word’s etymology in Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Law, however, we get closer to confirming what we’ve been suggesting all along: juris comes from the Latin genitive form jus meaning “right” or “law” and prudentia means wisdom or proficiency. Other sources show that prudentia has to do with foresight as well. Oh, and it is feminine in gender.

Jurisprudence without a feeling or value-attuned wisdom is not jurisprudence. One can argue then that alongside or even instead of the present-day “In God We Trust” there should be another phrase emblazoned on courtroom walls and that is “In Goddess We Trust.”

Wouldn’t this be appropriate? To pass by the statue of Themis outside, enter the inner sanctum of the courthouse, and see before us the phrase “In Goddess We Trust”? It is through just such experiences that we discover “the power of myth” still operating in our lives today.

——

On Monday: “In God/dess We Trust — Part II”