In the previous blog the phrase “restorative justice” referred to Mythfire’s contention that a balance between masculine and feminine, thinking and feeling must be restored to our contemporary understanding of jurisprudence. This “Myth & Justice” series as a whole has admittedly been a challenge and much has been left out or at best merely hinted at. Truly there is enough material for a much longer work on how a mytho-psychological toolkit could deepen both our understanding and our experience of justice.

In the previous blog the phrase “restorative justice” referred to Mythfire’s contention that a balance between masculine and feminine, thinking and feeling must be restored to our contemporary understanding of jurisprudence. This “Myth & Justice” series as a whole has admittedly been a challenge and much has been left out or at best merely hinted at. Truly there is enough material for a much longer work on how a mytho-psychological toolkit could deepen both our understanding and our experience of justice.

One of the ideas that hasn’t really been mentioned is that the spirit and heart-souls, or masculine thinking and feminine feeling functions, have negative poles just as they do positive ones. The extreme pole for thinking sometimes manifests as the reduction of data, or “facts,” to black and white, good and evil categories. This rigid worldview refuses to recognize that principles and values are only “eternal” in so far as they are eternally contingent on the circumstances of a given historical place and time.*

In contrast, the extreme for the heart-soul or feeling function can be characterized by the inability to see the forest for the trees, getting so caught up supporting this or that single value that the larger implications of such a one-sided view are overlooked. Or, equally possible, extreme “feelers” can be aware of so many potential values being in play in a given situation that it is nearly impossible to prioritize one value before another and then make a decision. The ideal, of course, is that thinking and feeling learn to work together which is no easy matter. (They also need to learn to work together with the other two psychological functions – intuition and sensation – which have unfortunately been entirely absent from this blog series.)

Next, Mythfire would like to summarize a few of the ideas from the “Myth & Justice” series as to how mythology and psychology might facilitate a deeper and fuller understanding of jurisprudence:

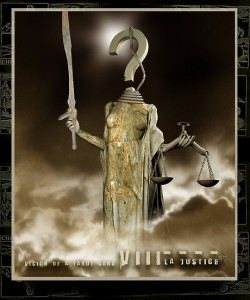

- Mythology: Jungian psychologist James Hollis writes that one way of defining myth is as “affectively charged images [. . .] which serve to activate the psyche and to channel libido in service to some value.” He continues: “We are never without myth, for we are never not in service to some charged image.”** This series has discussed the figures and myths of Themis, Athena, Sophia, and Wisdom. Much more could be said about these figures to connect them one to another and to the values that they have served since time immemorial. Certainly, the scales, blindfold, and sword of Themis are also images that could be opened up for further mythic illumination and explication. The same applies to age-old traditions such as mottos (“In God/dess We Trust”), court etiquette and customs (i.e. judicial robes), legal documents (From The Ten Commandments to the U.S. Constitution; also earlier and later forms of these same), and more.

- Psychology: Swiss psychiatrist C.G. Jung’s branch of depth psychology, called analytical psychology, has much more to say about how and why these energized mythic images (with their corresponding values) arise in the first place. Other topics that need further development include: a greater understanding on how typology, especially the thinking and feeling functions, impacts the judicial process in both positive and negative ways; how the feeling function is a value-based rational decision-making process; that opposites such as spirit-soul and heart-soul, masculine and feminine are natural energies within the human psyche, and how their tension might be held together and even transformed into something new via what Jung called “the transcendent function”; how this transcendent “something new” generally takes the form of an equally new and powerful symbol (After all, the images of Themis and her sword, scales, and blindfold arose in the first place and have remained for millenia because the psyche needed them then and still needs them now.); how Jung’s concept of the anima may be the feminine animating spirit behind more traditionally masculine endeavorssuch as the creation of law and order. (Though not mentioned by name in the “In God/dess We Trust” entries, the anima pervades these blog posts just as she does the very fact that most if not all virtues, i.e. Hope, Charity, Love, Prudence, Justice, Temperance, etc., have invariably been imagined as feminine in form. These archetypal soul ideas animate the movers and shakers [Zeus!] to create a world in which we can wisely live together in harmony.) Finally, depth psychology can yield a better understanding of how evolution occurs not only biologically but psychologically as well: that which was thought impossible, improbable, immoral, etc., in an earlier eon may in a later one be taken as part of [human] nature.

It has been said that “[c]oming to terms with the past has emerged as the grand narrative of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.”*** Once again, this “Myth and Justice” blog series has suggested that both mythology and psychology can help tremendously in this endeavor, especially if it involves a restoration of trust in the feminine as well as a more refined understanding of how feeling operates. In their book From Ancient Myth to Modern Healing, Pamela Donleavy and Ann Shearer go one step further by providing actual concrete examples of “restorative justice.” Facilitated by what are known as Truth Commissions, restorative (or transitional) justice helps two bodies of people – one an aggressor and the other the traumatized victim – through a process of reconciliation:

“By the turn of the 21st century, there had been more than 20 Truth Commissions across the world, from Argentina and Chile to Rwanda, Ethiopia and the Philippines. In the wake of the bloodiest century yet known, where 90 percent of the estimated 22 million people dead in conflicts were civilians, these commissions had become a crucial tool in ‘transitional justice’ from repression to democracy.” (112-3)****

The authors also include a very interesting quote from Archbishop Desmond Tutu on the subject of amnesty:

“Certainly amnesty cannot be viewed as justice if we think of justice only as retributive and punitive in nature. We believe however that there is another kind of justice – a restorative justice which is concerned not so much with punishment as with correcting imbalances, restoring broken relationships — with healing, harmony and reconciliation. Such justice focuses on the experience of victims; hence the importance of reparation.” (119)

In this quote, Tutu perfectly demonstrates how one may explain to a third party the symbolic figure of Iustitia or Themis without resorting to psychological or mythological jargon. “Correcting imbalances” corresponds to her balancing scales; “restoring broken relationships” to the sword that heals just as often as it destroys; finally, focusing “on the experience of victims” is practically a verbatim definition of the blindfold’s powers of vicarious introspection, a.k.a. empathy. In fact the whole process of restorative justice is arguably a kind of collective empathy.

It doesn’t seem possible or perhaps even desirable to do away with the adversarial approach to justice altogether (This adversarial approach is linked with “jousting” in earlier Mythfire posts). In fact, it is tempting to suggest, in keeping with Jung’s notion of the transcendent function alluded to above, that the figure of Themis, with her scales, sword, and blindfold, was a symbol that at some point in the past arose out of a state of extreme tension between these two approaches: adversarial versus restorative. Eye-for-an-eye retribution versus forgiveness and reconciliation. Or, put differently again, individual rights vs. communal/collective rights. This is territory that could bear further psychological exploration and discussion; this tension warrants continued holding.

Mythfire, however, quickly puts forward two additional thoughts regarding restorative justice:

- Restorative justice need not be restricted to something enacted by a Truth Commission. The recent official admission by the Russian Parliament that in 1940 Josef Stalin ordered the execution of 20,000 Polish citizens (most of them officers) followed a ceremony held earlier this year at the site of the crime. Both Russian and Polish officials were in attendance. Admission of guilt and jointly held ceremony are almost certainly examples of restorative justice.*****

- For that matter, restorative justice need not be restricted only to nations. Affirmative action, equal opportunity and other rulings so long as they correct imbalances, restore broken relationships, and focus on the experience of the victims, are all forms of restorative justice.

No doubt coming to terms with the past will continue to be part of the grand narrative of this century. However, the need to come to terms with the present and future is being forced on us more and more everyday. Toward this end, it may be appropriate to borrow an idea from the South African constitution: ubuntu. On a most basic level it means “a person is a person because of, through, other people.” (Donleavy and Shearer 114-115). To Mythfire, this sounds very reminiscent of the “values of relatedness” mentioned in the last post.

According to Donleavy and Shearer, “ubuntu permeates the country’s jurisprudence with three principles: communitarianism and emphasis on group solidarity rather than on individualism; conciliation and the restoration of peace rather than adversarial justice; and the promotion of the individual’s duty to the larger group rather than individual rights.” (116) In the United States in particular we have gotten away from the “we” and “people” of “we the people” or “a government of, by, and for the people” (from the U.S. Constitution and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address respectively). Rights are almost invariably spoken of in terms of individual rights, even when those individuals, as in a controversial Supreme Court decision earlier this year, are companies with their rights of “corporate personhood.”****** Other recent rulings in the U.S. maintain tax breaks for the wealthy and keep in place an estate tax, both of which will likely increase the gap between the rich and the poor. So many of us on some level feel that, deep down, we as individuals have the “right” to amass as much wealth as we desire and as much life, liberty, and happiness.

Two questions, then, to close: “When we are so focused on the rights of the individual, who is going to look after the rights of the people, i.e., the commonwealth?” Secondly, “What will it take for ‘we the people’ to decide to exercise wisdom, prudence, foresight and empathy — even if such a decision means sacrifices now so that a more prosperous and harmonious world can be realized tomorrow?”

The statuesque divine-like figure of Themis stands starkly by as if awaiting an answer to these and related questions. However, perhaps she herself imagistically embodies the way forward: her symbolically powerful scales, blindfold, sword, and feminine figure speak volumes if we would but listen.

——

This concludes the “Myth & Justice” series. Mythfire wishes everyone a healthy and joyous holiday season. See you in the New Year.

——

*Mythfire hopes to say more about principles vis-à-vis values in a future blog. For now, though, it will have to suffice it to note that a) examples given of values often show up elsewhere as principles and vice versa, and, more importantly, b) in any given situation there are invariably multiple principles or values in play. In both cases, the feeling function is then exercised to rank the values/principles in terms of importance (in other words value!) before a decision is made. In this and other ways, principles and values are both “contingent” on a time and place. More on what depth psychology has to say on these and other related terms (i.e. morals, ethics, conscience, etc.) as Mythfire moves forward.

** Hollis, James. Creating a Life: Finding Your Individual Path. Toronto, ON: Inner City Books, 2001, p. 44.

*** Kenneth Christie. Review of Meredith, Martin, Coming to Terms: South Africa’s Search for the Truth. H-SAfrica, H-Net Reviews. April, 2000.

URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=4008

****Donleavy, Pamela and Ann Shearer. From Ancient Myth to Modern Healing: Themis, Goddess of Heart-Soul, Justice and Reconciliation. London: Routledge, 2008.

*****http://www.foxnews.com/world/2010/11/26/russian-parliament-stalin-ordered-katyn-massacre/

Just thought you might like to know that I am here. It is good to see you have returned along this thread, as it is fun to browse through this and wonder, what is he talking about… No, seriously, I do follow it with great interest, when I’m not looking at other things.

Goddess? God is more than sex… I think. We divide ourselves into many different camps, with gender being the most basic. That’s why I always wanted to be gay, as a symbolic revolt against gender identity. Call it empathy, but I am not so altruistic. I am far too troublesome for that. Mostly, I just wanted to stir things up in my family.

So how was your holidays?

Caio