Discussing myth, religion or any other subject held sacrosanct by its adherents can quickly become a very serious matter indeed. Mythfire will strive to take a slightly different approach – a more playful approach. However, “play” here is meant in a particular way.

Discussing myth, religion or any other subject held sacrosanct by its adherents can quickly become a very serious matter indeed. Mythfire will strive to take a slightly different approach – a more playful approach. However, “play” here is meant in a particular way.

In his Foreword to Christine Downing’s Preludes: Essays on the Ludic Imagination, 1961-1981, David L. Miller writes that play in this sense does not have to do with fun and games:

“So what was the point of play? [Hans-Georg ] Gadamer asked me if I owned a bicycle. I said that I did. Then he asked me about the front wheel, the axle, and the nuts. He remarked that I probably knew that it was important not to tighten the nuts too tightly, else the wheel could not turn. ‘It has to have some play in it!’ he announced in a teacherly fashion…And then he added, ‘…and not too much play, or the wheel will fall off. You know….Spielraum, ‘play-room,’ some room for play” (ix-x).

Miller goes on, in describing Downing’s essays in her book, to write that play in this sense is not about “play as unseriousness, not about fun and games.” It is about “the space, the Spielraum, necessary for the wheel of life to turn soulfully” (x). According to Miller, in her essays Downing shows how this soulful play should be at work when discussing apparent opposites such as belief and disbelief, myth and reality, sanity and madness, age and youthfulness and more. The truth to questions such as “what is myth and what reality?” or “what is true sanity and what true madness?” cannot be found in once-and-for-all definite terms but lies somewhere in the middle of how the two terms are traditionally understood or defined.

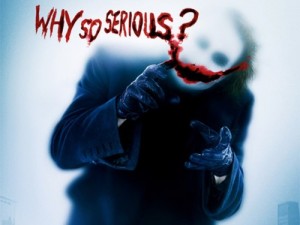

Another example is language itself, or word-play. The word “ludic” in Downing’s title, for instance, comes from the Latin word ludus which means “play.” So the ludic imagination is the one that has room for and makes room for play. More to the point, the ludic imagination is the one that is able to see play already at work in the many variegated ways life presents itself to us. (To draw from the field of cinema, one possible way of understanding the Joker’s line “Why so serious?” in The Dark Knight is that this is his response to the lack of ludic imagination in the very two-dimensional black-and-white characters he sees around him. They are too wound up, no room for play).

Jung writes:

“The forms we use for assigning meaning are historical categories that reach back into the mists of time – a fact we do not take sufficiently into account. Interpretations make use of certain linguistic matrices that are themselves derived from primordial images. From whatever side we approach this question, everywhere we find ourselves confronted with the history of language, with images and motifs that lead straight back to the primitive wonder-world.” (CW 9i, para. 67)

Toward this end, when discussing myth it may be good to always have in the back of one’s mind that the word myth comes from the Late Latin word mythos and the Greek muthos, both of which mean word, speech, or story. Also, in Mythography: The Study of Myths and Rituals, William G. Doty shows how there is a link between the root mu- in the word muthos with that of the Proto-Indo-Eurpoean root ma- which is associated with a baby’s first attempts at speech, specifically a cry for the mother’s breast (i.e. “Mama.”).

Therefore, when exploring myth as defined by Louise Cowan in the previous blog as an intuition, a shared response, and a cultural phenomenon replete with images, games, manners and codes, laws and customs, rituals, etc., it is also a good idea to remember “the primitive wonder-land” of myth, that is its original primal connections to first attempts at speech, to the deep-felt instinct to communicate urgent needs, and to the need for security and sustenance.

Finally, the words mythos and muthos have also been linked with our present day words mystery and muteness. Sometimes the ludic (or mythic) imagination stands before the Unknown and tells stories.

Just as often it stands before the Unknown in silence.

——–